SK Das’s literature of ‘Bharatvarsa’, Irrelevant to Modern Literature in India: A Critique

'Bharatvarsa' or 'the land of Bharata' is evident in a literary tradition in the Indian subcontinent since Vedic times. In contemporary times, Dalit writings have become a 'subaltern literature', incongruent with the idea of 'Bharatvarsa'. A critical analysis of SK Das's idea of literature. How long will it take to accept literature produced by Dalits in mainstream Indian literature?

|

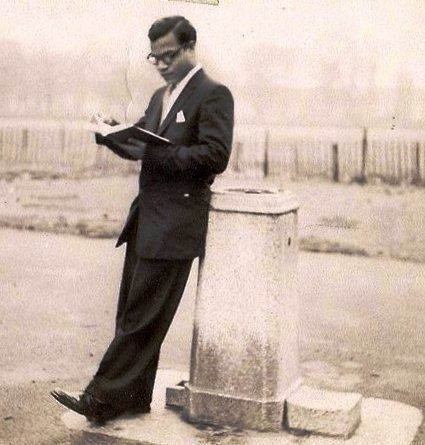

| Sisir Kumar Das | Picture Credits: Alchetron.com |

The Idea of Indian Literature

Only a few know about the case of 'Mudi Hindi' or the Hindi language taught to Dalits in schools which had Hindi alphabets reversed, so they had to learn a kind of reversed Hindi script in schools, which practically had no purpose after it. Historically, the Indian education system has been treating Dalit/Bahujan students comically in the name of learning unless there are schools run solely by our community.

A linguistic historian cannot assess a text in isolation of its language; it is often interdependent, a part of the history of the community. Indian literature is a record of memorable utterances of the Indian people. (Das, 1991, page 2)

The second issue we need to assess is whether it is mutually inclusive? Literature in India is, most of the time, mutually inclusive. The same tales pass on from generation to generation and are reimagined in texts of different examples.

One prevalent example is that of Ramayana, which has been re-told in a variety of ways all over the world, especially in the Indian subcontinent. The same character can be assigned to retellings of classic love legends of Romeo-Juliet, Laila-Majnu and Heer-Ranjha, all having the same characteristics. Folk tales of the Punjab-Haryana region, like Soni-Mahiwal, and Leelo-Chaman, are strikingly similar to the tale of Tantara-Wamiro in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India. This mutual inclusivity can be observed in different literary texts within India.

All of the examples mentioned above will have cultural differences, but the essence of the text will remain the same. This characteristic of mutual inclusivity has led Sisir Kumar Das to discuss the concept of 'Bharatvarsha' in the book History of Indian Literature.

|

| Sisir Kumar Das |

'Bharatvarsha' in Literary Texts

Indian literature is derived in theme and form from Sanskrit literature and Buddhist and Jain texts written in the Pali and Prakrit language, which are medieval dialects of Sanskrit. In Mahabharata, bharatavarsa, which translates to the land of Bharata, is mentioned as a geographical and cultural territory identified by its rivers and mountains. Bharatvarsa is mentioned in In the Hindu text, Skanda Purana (chapter 37). It is stated that "Rishabhanatha was the son of Nabhiraja, and Rishabha had a son named Bharata, and after the name of this Bharata, this country is known as Bharata-Varsha."[25]

In medieval times, Shankar Dev, an Assamese poet, invokes the idea of - dhanya dhanya Bharat Varsha. Similarly, Amir Khusro, another medieval Sufi poet, wrote a masnavi called Nur Siphir in which he talks about India. According to Das, there was a conception of the unity of India which prompted our poets to create a territory they described as 'Bharatvarsa'. Bharatvarsa is popularly mentioned in Bhagawat Purana.

He thinks of it as a unifying factor for literature in India.

However, his utopian idea of literature must explain the class and caste-centric education that has been prevalent in India since ancient times. Only a particular caste group was allowed to read and write for thousands of years, pushing most others (Dalits, Women, Tribals) to be marginalised in education. Thus, the literature that was produced (primarily the one written down) catered to a particular class (which, of course, had a few handfuls of caste groups). So how will this collective outlook flourish when millions of people are sidelined from the narrative of society as a whole?

Significance of this Idea in Literature Today

Munshi Premchand, in his presidential address at the first All India Progressive Writers' Conference in Lucknow in 1936, stated that realism in literature is a must. Literature must be reflective of the age. It should stop functioning as a narcotic for the people, a patronising agent of the privileged classes. (Premchand, n.d.)

Changing global scenario with the advent of the 20th century has shaped the literature of India remarkably. Literature produced during the Indian Independence Struggle relied massively on the themes of nationalism because it was the need of the time.

Invoking the idea of a 'bharatvarsa' was necessary to arouse the feeling of nationalism. Writers like Rabindranath Tagore, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya, and Bismil Azimabadi wrote to strike the nerves of the Indian masses.

However, it has been observed that, after the economic liberalisation of the 1990s, regional flavours have been lost in the Indian literary scenario. Writers now write with an international sensibility. Coffee-table books are more in demand to cater to the 'woke' culture of Indian readers of today.

Conclusion

In his book, S.K. Das tries to give the literature on India a collective identity despite its lingual and cultural differences. I agree with his notion of 'Sahitya as a unifying force'. Indian people with their activities and history, has had inclusivity to a certain degree. At the same time, a significant number of people were indeed barred from participating in the literary tradition of India since ancient times. The whole Dalit culture has been pushed to a subaltern level, unfortunately. However, Dalit, women and tribal writers are now coming into the mainstream narrative of Indian literature. I believe that we are gradually moving towards the idea of Indian literature, which is different from the idea that Das has explained in his book.

Das, S. K. (1991). A History of Indian Literature (Vol. VIII).

Mukherjee, S. (2015, April Monday). The Idea of an Indian Literature. UoH Herald. http://herald.uohyd.ac.in/the-idea-of-an-indian-literature/

Premchand, M. (n.d.). The Nature and Purpose of Literature. Social Scientist. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23076335?seq=1

Comments

Post a Comment